NO PATHWAY HERE

by John H Marsh

CHAPTER XIII

"OPERATION SNOEKTOWN"

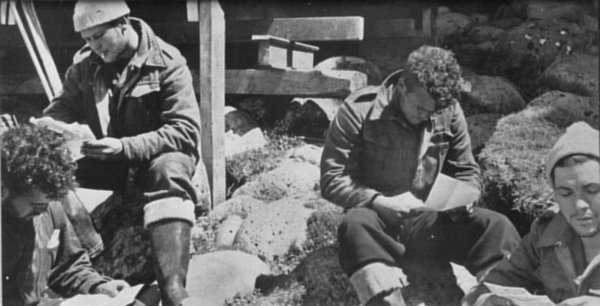

"We had brought their mail with us . . . "

Early the next day there was a meeting in the office of the Secretary for Transport to discuss a detailed plan of action. It was attended by Mr. C. Coghill, the Under-Secretary, and representatives of the Meteorological Department and of the Civil Aviation Telecoms Department. At this meeting the decision was taken to appoint the Chief Engineer of the latter department, Mr. G. A. Harvey, as Co-ordinating Officer. It was also decided to invite Mr. Allan B. Crawford to take charge of the expedition. Volunteers to join it were to be called for from the Meteorological and Telecoms Departments. All these were to be brought together in Pretoria by the following morning.

Immediately this meeting broke up its participants got busy on the telephone, telegraph line, and radio. They allowed neither difficulties of communication nor distance to deter them from getting the men they wanted.

The king-pin of the expedition was to be Crawford - a man peculiarly fitted by circumstance, temperament and experience for the leadership. He was the only man known to the authorities in the Union who was so well qualified to undertake this task. They were faced, however, with more difficulties in trying to get him than any of the other men they needed, for he was on Tristan da Cunha, where ships normally call only once a year. There was two-way radio communication between the Union and the island, but the limiting factor in making the best use of this facility was the need for keeping the plans secret from the radio staffs while still getting enough information through to Crawford to enable him to make a decision. Code could not be used as Crawford had no key.

This is how the call to leadership eventually reached Crawford - in probably as unconventional a manner as such an invitation has ever yet been extended to any man.

As the first necessary step Mr. Gibson by long-distance telephone called up the Civil Aviation Division's principal air traffic officer for the Cape, Mr. George L. Williams, who was in charge of the Wingfield radio station at Cape Town. After emphasising the highly confidential nature of the communication he dictated a personal message for Crawford. He instructed Williams to pass it across himself, after ensuring that he was alone at the instrument board and could not be overheard.

When Tristan came on the air for its next schedule early that afternoon, the operator took down a message instructing him to call Crawford. On arrival Crawford was handed another message requesting that he evacuate all the radio station staff and take over the instruments himself. Crawford had only a rudimentary knowledge of Morse, but it so happened that an indelible impression had once been made on his mind when he watched one of the most senior British naval officers, who wished to deliver a highly confidential message, himself manipulate the Morse key with the confidence of one fully trained to use it. Though he had already earned a reputation in the separate fields of surveying, meteorology and authorship, that incident had opened Crawford's eyes to the value of a knowledge of signalling and he had determined to learn it at the first opportunity. The chance had come only about two months previously. He had found time on his hands and two of the island children, aged 10 and 11, who had been taught semaphore as Girl Guides, had gladly consented to try to pass on their knowledge to him. Faithfully they had been coming along every Sunday to give him their hour's instruction.

Before he turned to the instruments Crawford disconnected all leads from the transmitting room to other parts of the building. Then he decoded Williams' first signal. "Are you alone?" He gave the affirmative, then took down: "What follows is top secret. You are to tell no one of it and discuss it with nobody. The Prime Minister requests you to lead expedition to establish meteorological stations. Cannot disclose where. Will require you for about twelve months ... "

By now excitement had so distracted Crawford that he could no longer cope with the stream of dots and dashes coming over the air, and for a while he lost the thread of the message. He calmed himself and was able to resume: "Personally hope you accept as consider it an honour that man from Department Transport asked to lead this expedition. What is your decision? Signed Gibson Secretary for Transport."

As the meaning of this surprising message became clearer, Crawford realised that it was a matter of considerable personal import.

The dots and dashes spelled out that he could have until the next schedule in 20 minutes' time in which to make up his mind.

He did not take all that time to come to a decision. As soon as communication was re-established he tapped. out "I accept."

While the exchange of messages with Crawford was going on other men who had been invited to volunteer for the expedition were already preparing in various parts of the Union for a dash to Pretoria to the rendezvous ordered for the morrow. By road, rail, and air they hurried to the administrative capital. They started from places as far apart as Bloemfontein, Pietersburg, and Cape Town. The Cape Town man was given a priority seat on the mailplane at 5 p.m., and was in Pretoria the same night.

The next day Mr. Gibson interviewed the meteorological and telecoms personnel, and, without telling them where they were to be sent, warned them that they would have great hardships to face and must be prepared to remain in exile for a year if necessary. Given the chance to reconsider not one withdrew his request to be allowed to join the expedition. Finally D. O. Triegaardt, of Benoni, was chosen as Assistant Meteorologist to Crawford ; C. O. Hawkins, of Bloemfontein, as telecoms technician in charge ; and J. A. Bennetts, of Pietersburg, J. Fenton, of Cape Town, and D. C. K. Esterhuize, of Calvinia, as telecoms operators. Hawkins and Bennetts had previously spent a year on Tristan da Cunha with Crawford. All those chosen were unmarried ex-servicemen.

While the civilian volunteers were being chosen at the offices of the Department of Transport, others to form the party which was to erect a settlement on the islands before the coming of winter were being selected from the Permanent Force at General Headquarters.

In drawing up their plan the authorities were severely handicapped by the lack of knowledge of conditions at the islands, and by the fact that South Africa had never before initiated and equipped an expedition of this nature to go into the Southern Ocean. With the assistance of the State Library in Pretoria public libraries throughout the Union were scoured for books dealing with the islands. It was necessary, in order to camouflage the real object of the search, to ask for literature on other islands, and on the Southern Ocean, and the Antarctic generally as well. Of great help was a collection of extracts from books bearing reference to Gough and Marion Islands which had been compiled by Major Beadle and Crawford, assisted by other members of the meteorological section of the S.A.A.F. in 1945.

A cable was sent to South Africa House in London asking that authorities in Britain should be consulted on the supplies and equipment, particularly in the line of food and clothing, that the expedition should take with it.

On Saturday, December 20, the Public Works Department decided that weatherboard hutments should be used for the settlement on the islands. That same morning the Union Defence Force authorised that six huts which appeared to be suitable should be taken from the grounds of General Headquarters. They had been erected during the war and were now surplus to requirements. Mr. A. D. McKay, the District Representative of the Public Works Department, ordered his staff to work throughout the week-end, if necessary, on this job. Immediately after lunch demolition gangs arrived at General Headquarters and began to dismantle the huts. Some were still being evacuated by their occupants. One typiste in uniform suspended her frenzied packing in order to chide the intruders who were trying to hurry her out. While she raged the roof was lifted off and by the time she had decided it would be better, perhaps, to forget her dignity and salve what she could, the sides of the hut also were down and she was standing helplessly beside her desk in a great open space, to the amusement of many lookers-on.

As soon as the huts were down carpenters began modifying and strengthening the sections to enable them to resist high winds, and insulating them against cold. At the same time architects were at work on the internal layout of the huts to adapt them for sleeping and working quarters. They had undertaken to have full detailed plans ready by the following Monday.

On Sunday, December 21, while the Transvaal was leaving Cape Town for the islands, Harvey drafted the operational order delegating responsibility for supplying specific items to the Union Defence Force, the Public Works Department, and the Department of Transport.

The Defence Force was to be responsible for providing the ships, special clothing, aviation signalling lights, cooking and heating utensils, and all medical supplies. Brigadier W. H. du Plessis, O.B.E., of the South African Medical Corps, himself compiled the list of medical requirements. As the expedition would have to be in all respects self-contained, the Army personnel had a blood check taken - this was to allow transfusions to be carried out, if necessary. A sample of each man's blood was taken and tested, and it was thus possible to ensure that every type of blood was represented by at least two individuals in the party.

The Public Works Department was given responsibility for providing all accommodation, cooking and heating facilities, and for packing the expedition's equipment. Packing required the most detailed planning and meticulous checking. Many thousands of packages had to be made up. They had to be small and of comparatively light weight to facilitate handling. They had also to be able to endure repeated rough handling. Every package had to be prominently and durably marked on every side to allow of easy identification.

The Department of Transport was given the job of providing all communication systems, power, lighting, and meteorological equipment. It was also to make all arrangements for the welfare of the men forming the expedition. As there was doubt whether local fuel supplies would be available, it was to provide wind- driven generators, which would be independent of fuel.

Arrangements for the correct type and quantity of food that would be required were of the utmost importance, and must be put in hand without delay. Harvey obtained the list of foodstuffs and quantities that were sent annually to the meteorological party on Tristan da Cunha. By borrowing from the libraries Shackleton's Quest and other books on Polar exploration, he was able to compile a list of what would probably be most useful to the expedition. This was checked and supplemented a day or two later with information sent out from London by Mr. A. M. Hamilton, of South Africa House. Mr. Hamilton, as a result of the request from Pretoria, had spent that historic week-end of December 20-21 going through the records of the Scott Polar Research Institute at Cambridge under the guidance of Dr. Brian Roberts, the scientist on the staff of the Institute, who himself had considerable experience of Polar exploration. Hamilton passed on from Roberts detailed suggestions on the foodstuffs, heating facilities, and accommodation that should be provided for an expedition such as that envisaged. He also made suggestions on the types of personnel that could usefully be included. Unaware that he had already been approached, Dr. Roberts recommended as a suitable surveyor for the expedition Mr. Allan Crawford, "who has already made a name for himself in work of this sort."

On the Monday plans for the accommodation on the Island were complete. The Public Works Department put their Pretoria workshops on a 24-hour basis, with two shifts each working 12 hours, in order to cope with the large amount of construction work required. The P.W.D. decided to' undertake the packing for all departments concerned, except that of the medical supplies. A rough check showed that at least 300 tons of equipment would have to be shipped. The S.A.N.F.'s frigates were unable to cope with such a large quantity, and after some negotiation the Government Guano Islands Department's coaster Gamtoos was chartered to act as store-ship. A special train would be required to carry the supplies from Pretoria and Johannesburg to Cape Town. The South African Railways agreed to provide one and to make all necessary arrangements for the fastest possible journey to the Cape. Loading of the train was to begin on the following Monday, December 29.

There were not in the Union men who could qualify for membership of the expedition in the essentials - single, healthy, and of equable temperament - who were also experienced in boat-handling. Boats would be essential for communication between the islands as well as for fishing. Mr. Gibson therefore asked Crawford to try to obtain six volunteers from among the Islanders to go with him on the expedition. The task thus given him was not an easy one to fulfil. All the Islanders had been born and bred there in a self-contained community, and only one or two had ever seen anything of the outside world. Their knowledge of other peoples and places was confined to what they had seen from the crews of passing ships and the few visitors they had from time to time been hosts to ashore. The suggestion Crawford now put to them, that they should leave their island home and go out into the world, was therefore a startling one. What made it all the more surprising was that he frankly confessed that he did not know where he would be taking them, nor anything else about the region they would go to, except that it would be very cold. But nobody else had ever proved his understanding and appreciation of the Islanders by withdrawing from civilisation three times in order to live with them as Crawford had done. Their confidence in Crawford, therefore, was such that he was able to report within a few hours that he had found six volunteers who might be suitable, but that they were all married. It was then decided in Pretoria to waive the restriction on married men joining the expedition, as far as the Tristan Islanders were concerned. Arrangements were made with the High Commissioner for the United Kingdom, which administers Tristan, to reimburse the Islanders in cash and kind (the humble but much-used potato is the principal medium of exchange on the island). Suitable provision would also be made for the families of the volunteers while they were away. Besides serving as boatmen and fishermen the Tristan volunteers would be general handymen while with the expedition. It was felt that their experience under conditions that were as nearly as possible similar to what they would face at the Prince Edward Islands would be valuable.

Crawford was told to be ready, with his Islanders, in the next two or three weeks when the frigate Good Hope would arrive to fetch them. She would bring with her reliefs for the meteorological staff and supplies. Crawford was to endeavour to obtain two of the famous Tristan canvas boats, which were specially designed for operating from surf-swept beaches. The Islanders built them themselves almost entirely out of material bartered from visiting ships. They had only a few, and they were their most prized possessions. They had no use for money, and would not sell any of their boats, but Crawford was able to arrange a barter deal, under which they agreed to dispose of two of their boats in return for the material for building four others. The Good Hope would bring the materials from Cape Town and return with the boats and their crews.

Since all accounts agreed that there was no palatable food, either meat or vegetable, to be found on the Prince Edward Islands, the authorities in Pretoria were anxious to import on to the islands bird and animal life that was edible and might be able to acclimatise itself. They therefore instructed Crawford to bring back with him a small flock of Tristan geese with which they hoped to establish a colony that would provide duck eggs as well as young birds as additional items of diet to the "hard tack" rations on which the islands' permanent staff would have to live.

In Pretoria 200 men were now working day and night on the equipment for the expedition. They stopped only for a 12-hour break on Christmas Day. On Boxing Day it was decided that a step-up in the effort in the workshop was required. Thereafter the men worked 15-hour instead of 12-hour shifts. Though none knew the real objective all realised that they were working on something of great importance and that theirs was a vital part in it. The realisation spurred them on.

It was by now obvious that if the normal procedure for authorising and purchasing the expedition's requirements were followed it would not be ready to sail for months. "Red tape" must be dispensed with. The Prime Minister gave the necessary authority, subject to certain safeguards, and the biggest brake on speed was thereby eliminated. Harvey interviewed the Union Tender Board on December 27, and as a result the Board decided to send a representative to Cape Town at once by air to purchase all the foodstuffs required for the expedition there. This would avoid unnecessary transportation.

Arrangements for sea transport to the islands had by now been lined up. The frigate Natal was to leave Cape Town on January 7 to take over from the Transvaal as guard-ship. The Gamtoos was to follow her on January 12 with the construction party and all the equipment and stores. So carefully was everything planned in advance that even the berth at which the Gamtoos was to load was chosen several weeks ahead. To reduce to the minimum the risk of misdirection, on every package was stencilled the inscription : "Met. Officer, Snoektown, No. 4 South Arm, Table Bay Docks."

Loading of the special goods train began in the Pretoria goods yard, on December 29, to schedule. There was still so much to be done, however, that it became evident that a further increase in output was essential if the train was to depart on January 6, as arranged, with all the equipment on board. The Public Works Department tried to meet the need by providing sleeping bunks and canteen meals at the workshops. The men now ate and slept alongside the job. Rest periods were limited to four hours in every 24. Seldom, even in the most critical periods of the war, had they been called upon to make such an effort. The pace was killing and they could not have maintained it much longer, but they had the satisfaction of seeing the last package trucked on January 6 - the deadline date.

Even the loading of the train presented special problems. The Railways had promised to give it passenger train priority, and to have it alongside the Gamtoos on the night of January 9. It was scheduled to do the 1,000-mile journey in about one-third the time normally taken by goods trains. One truck containing cement was re-loaded four times before the experts were satisfied that it was properly loaded for such speed. Each of the hutment sections had to be carefully braced in its truck, and some which were found to be too big to pass through the tunnels en route had to have their "footings" lopped off.

On the afternoon of January 6 the train pulled out of the Pretoria goods yard.

The next day all the men who were going on the expedition were put through a stiff medical examination by Brigadier du Plessis. They were inoculated against fever, and each man who used them was supplied with a duplicate of his spectacles and dentures. Two days later two Air Force Dakota transport planes flew the Army personnel from Potchefstroom to Cape Town. At the same time Harvey and the Public Works Department's Pretoria District Representative, Mr. McKay, flew by civil plane to Cape Town to supervise the transhipment of the expedition's equipment from the special train to the Gamtoos. They were accompanied by Mr. H. P. Dike, the P.W.D.'s Senior Works Inspector, who was going to the Islands to supervise the erection of the settlement.

The special train reached Cape Town Docks safely that night.

Copyright Mike Marsh (2025)