NO PATHWAY HERE

by John H Marsh

CHAPTER XXV

LOOKING AHEAD

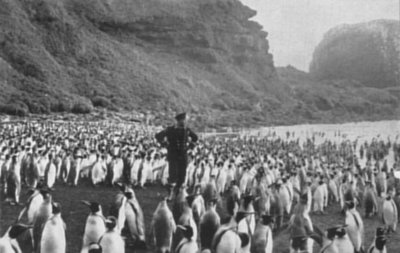

Thousands of King penguins on the beach of Ship Cove gather

round to discuss the first man they have seen.

That step was proof that she is not only alive to the need for self-protection in these days when whole nations that go unprepared can disappear overnight, but it is proof also of a wider interest that desires to see stability in the southern hemisphere ensured and all nations below the Equator eventually enjoying the benefits of accurate long-range weather forecasting from the Southern Ocean and the Antarctic Continent itself.

Neither of these aims can be fully realised until the right to possession of all territories in the south is fully investigated and internationally agreed upon. The sooner the nations get together on the subject the better it will be for the future peace of the world. The best solution may be a general trusteeship by the United Nations of all territory within the Antarctic Circle.

South Africa must play a leading part in these discussions. Territorial ambitions have never been hers, but the development of world warfare and transfer to the air of the principal media for waging it have forced her into a vital strategic position.

If war comes again it will almost certainly be fought mainly in the air. But troops to occupy strategic positions and supplies to support them will still be needed. Such a war, as far as one can see, must be inter-continental. And since the Mediterranean will again be closed to free passage and the Panama Canal will probably quickly be put out of action, and the passage round South America is too stormy and insufficiently serviced with port facilities, most of the shipping travelling between east and west will be forced to do so round the southern end of Africa. The waters south of the Cape will become the principal gateway between the Orient and the Occident.

As in World War II, this concentration of shipping will make these waters a battleground again - but the fight will be fiercer this time, for on its outcome more will depend than in previous wars. And whether she wants it or not the Union will be drawn into the conflict. Geographically she is in too vital a position, commanding the ocean crossroads as she will be; for the combatants to allow her to stand aside and deny either side the use of her ports and airfields. Whichever side she supports she will have to expect heavy attack from the other.

One of the principal weapons that the attacker will probably rely on will be guided missiles. If he can establish himself within range of South Africa's seaports and also of the shipping passing round the Cape, he should be able to do terrific damage, and might even succeed in bringing to a stop the movement of ships between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

The islands of the Southern Ocean offer him commanding sites for his launching platforms. A semi-circle of them is strung around the Cape at just the right distance to enable him to strike while being comparatively safe from effective retaliation.

At the western end of the semi-circle lies Tristan, some 1,700 miles from the nearest point of the African coast at Cape Town. A little further south is Gough, 1,550 miles from the mainland. Almost due south of the Cape is Bouvet, 1,400 miles distant. Then, to the south-east, we get the Prince Edwards, about 950 miles from the Algoa Bay coast. Finally, further to the east, there lie the Crozets, just under 1,400 miles distant from East London.

If all these islands are not within range of rocket attack of the African continent, there seems little doubt that they soon will be, at the rate that rocket missiles are now being developed. Even Australia's 1,000-mile rocket range, though still under construction, is already being criticised as being too short for full-scale experiments. Three-thousand-mile rocket flights are no longer just a scientists' objective, for ample evidence has now come to light that up to the time of her collapse Germany was seriously planning and making good progress in her preparations for bombarding the American continent with V-weapons fired from Europe.

By her successful occupation of Marion South Africa has demonstrated that with determination and the right equipment it is possible to land all the men and supplies that are desired on even the most gale-swept of islands.

The whole semi-circle of islands round South Africa, therefore, are a potential danger to her and to the peace of the world, so long as they remain available to abuse by the enemies of peace.

Of all these islands, only Tristan and the Prince Edwards are inhabited. None of the others have in fact ever been effectively occupied by their claimants. Britain claims Tristan and Gough, Norway claims Bouvet, and France claims the Crozets.

Geographically all of them should be considered as belonging to the Union of South Africa, she being the nearest inhabited land mass to them. They are in the position of southern guardposts of the African continent.

Strategically, also, they should be considered as belonging to this continent. They are an essential part of its defensive system. In the wider field that whole system is vital for ensuring world peace.

With the exception of Britain, none of the claimants are able or apparently interested enough to attempt to occupy and effectively administer (which must mean effectively defend also) their islands. Norway is more than 8,000 miles from Bouvet and has no overseas colonies. She claims no territory in the southern hemisphere apart from Bouvet and part of the uninhabited Antarctic continent. None of which, of course, should detract from appreciation of her outstanding record of exploration and research in the Far South. But the point is that Bouvet appears to be of no practical value to her, and she has made no attempt to make any use of it.

France has stronger claims to possession of the Crozets in that she has other colonies in Madagascar and Reunion, which are approximately the same distance from the Crozets as the Union is, while her nationals did, during last century, temporarily occupy and make use of the islands while engaged in sealing. But Madagascar and Reunion are themselves only weak colonies that cannot help in the defence of the Crozets. The motherland is 8,000 miles away.

Nobody would question Britain's right to possess Tristan. She has effectively occupied and administered it for well over a century, and its inhabitants are happy and loyal under her rule. Nobody is better able to look after its defence, either. But it has no peace-time value for Britain, and administration of it must become progressively more difficult from London, while, fortunately, it becomes easier from Pretoria.

The growth of its population is the chief cause for concern. When it was smaller it was able to support itself from its own production of food, supplemented by bartering from numerous ships - chiefly whalers and sealers - that used to call. Now it has outgrown the productive capabilities of the island, and ships no longer call to barter. The islanders are forced to depend largely upon charity sent to them from Britain and the Union. Warships have to be sent once a year from the Cape to take them supplies. They bring nothing back in return.

The population is now so big that a substantial section of it will soon have to be evacuated unless the Governments concerned are prepared to extend their philanthropy even further and are ready to send ships with additional food supplies whenever the potato crop fails and food runs short on the island. South Africa is the only country that can assimilate the Tristan islanders in its population. They trace their descent back through the St. Helena women to women who went from the Cape to settle on St. Helena. When, more than half a century ago, it became necessary to reduce the population of Tristan just as it is now, the emigrants were brought to the Cape and eventually became harmoniously absorbed into the local population.

With the growth of population and the change in outlook that has come about through closer contact with the outside world, the islanders require now a resident civil official rather than a minister of religion, as in the past, to administer their territory. A South African, with his better knowledge of their background and characteristics, should be best able to understand and guide the islanders in civil matters.

Tristan's links with South Africa were forged more closely when the Union's meteorological station was established there, and the South African Naval Forces at the same time took over from the Royal Navy the responsibility of providing transport for reliefs and supplies.

Early in 1948 these links were strengthened when the South African ship Pequena carried out a thorough investigation into the fish resources of the waters of Tristan and its neighbouring islets, and also of Gough Island. As a result a group of South African companies in which the Union Government is financially interested announced on the Pequena's return in March that they had applied to the British Government for a concession to develop fishing commercially there. They plan to erect canning factories and to create a large export trade. Labour may have to be imported to assist. This is added reason for hastening the establishment of an effective civil administration on this island which has neither monetary system (a potato ranks as the equivalent of a farthing) nor postal service (letters are carried free by sympathetic shipmasters). The time seems thus to be appropriate now for South Africa to accept full responsibility for Tristan, if Britain is prepared to cede it to her. In that event Britain would probably be willing also to transfer her rights over Gough. Since Norway and France have apparently no very great interest in Bouvet and the Crozets respectively, and would in any case have some difficulty in satisfying the appropriate authorities that they have fulfilled all the conditions of annexation required by international law, they should be prepared to discuss the cession of their rights in these territories to the Union. They would no doubt take into account the advantages to the maintenance of world peace and the material benefit that would eventually accrue to so much of mankind were the Union to occupy them effectively and to establish permanent meteorological stations on them. South Africa would fail in her duty to the world were she not to follow up such opportunities. She should own these islands on her doorstep and insist that they do not come within the scope of the proposed trusteeship agreement for the Antarctic proper. She cannot afford to risk finding herself hamstrung when it comes to fending off a threatened attack.

Thus the pathway that at last has broken through to Marion and Prince Edward leads on.

Copyright Mike Marsh (2025)