NO PATHWAY HERE

by John H Marsh

CHAPTER V

SEALERS AND SURVIVORS

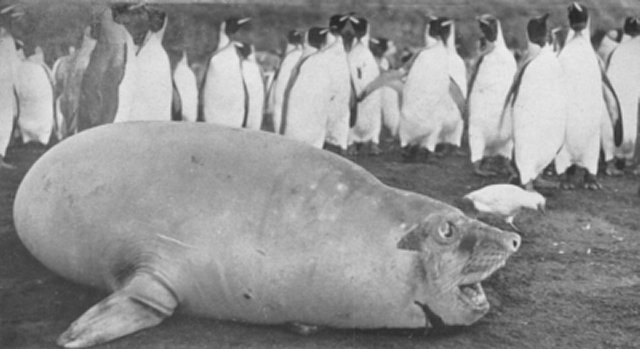

A small female sea-elephant with King Penguins (so rare that the London Zoo has paid up to 250 Pounds each for

live specimens) and a little Sheath-bill found only on the Prince Edwards.

The sealers came from Cape Town, England, America and Nova Scotia. The Cape Town ships made almost annual voyages to the Prince Edwards and the Crozets. Those from other countries often voyaged via the Cape Verdes or St. Helena, Tristan, the Prince Edwards, the Crozets, Kerguelen, Amsterdam and St. Paul, and thence to a South African port to unload their cargoes of oil and skins before making another round of the islands on their way home. In time they killed off practically all the fur-seals and greatly reduced the numbers of sea-elephants and sea-leopards, as well as the penguins. Early this century there were still two little two-masted schooners making the round of the islands from Nova Scotia and putting in at Durban once or twice a year to tranship their skins to the Britain-bound mailships.

In 1906 a Norwegian schooner called the Catherine, which had been fitted out at Cape Town for a whaling research voyage to the South Indian Ocean, was wrecked at the Crozets. Her master, Captain Ree, aware that it might be years before a ship came this way, set out in one of the ship's boats with some of the survivors, to sail more than 3,000 miles to Australia to fetch help for the remainder. They eventually fell in with a German sailing-ship which landed them in West Australia. Cabled arrangements were then made for the Cape Town coasting steamer, Ingerid, to proceed to the Crozets and pick up the survivors. She found they had already been rescued, however, by the New Zealand-bound liner Turakina. Captain Ree's men owed their lives in the first instance to the provision and clothing depot left on the island specially for the benefit of shipwrecked crews by the British warship Comus, 26 years earlier. They had used up most of the food and clothing. The Norwegian Government therefore arranged to replenish the depot, and on his return home Captain Ree was given command of the sealing steamer Solglimt and sent back to the Crozets to perform this duty at the same time as he carried out sealing.

In October, 1908, Ree brought the Solglimt into Port Natal on his second voyage in her to the Southern Ocean. This time he was going to the Prince Edwards. His ship aroused considerable interest at Durban, for she was one of the best-equipped sealing vessels afloat. She had been built at Sunderland in 1881 and was of 1,810 tons gross, 271 feet long, and drew 20 feet of water. Her crew numbered no fewer than 70 men. She was owned by Storm, Bull and Company of Christiania and was supplied for a voyage of many months, having large quantities of provisions on board and 900 tons of coal in her holds to supplement her normal bunker supplies.

Leaving Durban on October 5, she made her landfall at Marion Island ten days later. Finding the weather favourable, she began operations immediately. The landing places were teeming with sea-elephants. On that first day her landing parties killed all they found on the beach.

On the next day Ree hoisted anchor to proceed to the landing place used by the Challenger and repeat the performance. He was navigating in what the chart showed to be deep water, two miles from the shore, when the ship shuddered violently and listed as she scraped over a pinnacle of rock. Water gushed in through the torn plates and Ree had time only to race for the landing place and ram his bows on to the steeply-sloping beach before his ship filled and settled on the bottom. The Norwegians were now in a serious plight, for their ship was liable to break up at any moment, there was no shelter ashore, and there was no knowing how long it would be before the next vessel came to the island. Their first preoccupation, however, was to get ashore with as much as they could save. They filled the boats with food, sails, spars, tackle, and anything else that might be handy, and eventually succeeded in getting all on to the beach, though not without great difficulty and some danger owing to the high seas that were running into the cove.

The elements were kind to the castaways, however, for the Solglimt did not break up until they had transported ashore about ten tons of provisions and large quantities of useful equipment, including ropes, tarpaulins and timber. Then the vessel broke in two and slid beneath the surface, leaving only the tip of her stem above the water.

With the gear they had salved the men were able to make themselves tolerably comfortable, their salvage being supplemented by more timber washed ashore after the sealer broke up. Under Ree's direction they began the erection of a small village, with a timber hut for every four men and a large one in the centre to be used as a cookhouse and storeroom. They chose a site on a rise above the beach, close against the cliff which sheltered them from the westerly winds.

Although there were 70 men to feed they had enough provisions to free them from worry about possible starvation. In any case they could live on the sea-elephants and bird-life if need be.

Ree determined to attempt a repetition of his small-boat voyage affer his previous shipwreck at the Crozets, and he began to fit out one of the lifeboats for a voyage to the Cape or Australia. He knew there was small chance of making the 1,000-mile passage to the African coast against the prevailing westerlies, but he planned if this proved impossible to turn and run with them the 4,000 miles to Australia. But Marion's castaways were to be better treated in all respects than those who had so far come ashore at Prince Edward. They had only been on the beach a month when two ships hove in sight.

The visitors were the 100-ton Nova Scotia schooners Agnes G. Donohue and Beatrice L. Corcom, and they had come to top up their tanks and holds with oil and skins before proceeding to Cape Town to tranship their cargoes. Each was manned by 15 men, who were not a little surprised to discover this well-populated village on what they had believed to be an uninhabited island.

The masters of the schooners readily consented to tranship the survivors back to civilisation, though in order to take his quota of 38, including the Solglimt's master, Captain Balcom of the Donohue had to maroon six of his own men on the island, promising to return for them later. He landed the rescued party at Durban on November 30. The Corcom arrived with the remainder four days later. From Durban the two ships sailed back to the islands.

Lloyd's agent, cabling from Durban the news of the Solglimt's loss, reported that there was no hope of further salvage from the wreck. He had dutifully hawked the casualty among local salvage contractors, but he concluded his cable apologetically with the statement: "Cannot get an offer."

So there still lies on the bottom of Ship Cove (or, as it is now sometimes called, Solglimt Cove) 900 tons of good coal for anybody's taking.

In May, 1909, six months after the rescue of the Solglimt's survivors, the first steam sealer from Cape Town went down to work the Prince Edwards. She was the tiny converted trawler Victoria (Captain Carl Olsen), owned by Messrs. Irvin and Johnson's Southern Whaling and Sealing Company, which had obtained a sealing concession from the British Government.

Less than a year later, in March, 1910, the islands were examined by the steamer Wakefield for traces of the lost liner Waratah and her complement of more than 200. The Waratah had vanished during the coastal passage from Durban to Cape Town in July of the previous year. The Wakefield sent a search party ashore at Ship Cove, but found no sign of people from the missing vessel, and no trace of the Waratah and her complement was in fact ever found.

The search party found that Ship Cove was almost blocked by the submerged hulk of the Solglimt. On the beach were three boats, hauled up out of reach of the sea, and three iron blubber pots, together with a quantity of timber. The huts built by the Solglimt's survivors were still standing, one fitted with tables and chairs and the storeroom containing a cooking stove and large quantities of provisions. Half a mile further along the coast to the west were the remains of huts that had apparently been used by parties collecting penguin skins.

Another notable explorer, Roald Amundsen, passed by the islands in November, 1911. He was racing Scott to the South Pole, however, and did not want to risk delay, so he made no attempt to land. History has told how he beat Scott by five weeks and became the first man to reach the bottom of the world.

In October of the following year the Cape Town sealing schooner Seabird, owned by Irvin and Johnson, landed four men on Marion Island to serve as watchkeepers and prevent poaching, and then went on to Prince Edward to start the season's work. Her auxiliary engine broke down but she made the island under sail and anchored for the night of October 21 off its eastern side.

Early the next morning a sudden south-easterly gale caught the ship before she could claw out and drove her, dragging her anchors behind her, on to the lee shore, just as had happened with the Maria near the same place years earlier.

She struck about 100 yards from the land and began to fill rapidly. The majority of the crew got away in three boats, hurriedly stored with provisions, but Captain Hystad and two of his men had to jump into the freezing water and swim to them as the Seabird rolled over and sank.

Heavy seas made landing impossible on this side of the island, and the 22 men in their boats had to row right round to the other side, where in the lee of the high cliffs they were able to get ashore and haul their boats out of reach of the waves. Then, wet and shivering with cold and burdened with the weight of the provisions and a small tent that they had been able to save, they toiled over the 2,000-foot mountain back to the eastern side of the island where they knew shelter was to be had in the big cave. They reached it after dark, completely exhausted. They made a fire from the blubber of a sea-elephant they had killed, and tried to dry their clothes. Then they lay down on the damp ground, close together to try to retain their body warmth, and with only the tent canvas as a covering slept fitfully.

In the morning one of the men, Andersen by name, was missing. He had been seen to leave the cave during the night and had apparently not returned. They found him at a nearby stream. He lay with his head in the water, dead. A deep wound in his forehead suggested that he had missed his footing in the darkness and in falling had struck his head against a stone. Then while probably unconscious he had rolled into the water and been drowned.

They buried him nearby in a shallow grave that they scraped out of the soil with their hands. They had no Prayer Book and nobody knew the words of the Burial Service. But they all stood round the grave, bare-headed and ragged in their sea-stained clothes, while their captain "just said some vords to Gott" as one of the Norwegians put it simply in his broken English later.

They had saved enough provisions to last them a month, and they eked them out with a supplementary diet of sea-elephant, bird flesh and eggs. At the end of six weeks, however, their supplies were running out, and Hystad and three companions therefore set out in one of the lifeboats for Marion Island, where the four watchmen had been left with a fair supply of flour and other provisions.

The crossing took five hours. The watchmen rejoiced to see them still alive, and made them comfortable in the Solglimt's huts. Twice they tried to sail back to Prince Edward with their boatload of supplies, but after covering only a mile or two were driven back by sudden storms that all but swamped their tiny craft. They were still on Marion when Christmas came. In the third attempt they succeeded in crossing the channel, and after their absence of more than three weeks they found their shipmates showing signs of semi-starvation. The fresh supply of provisions had come just in time.

As the months went by they tried to fill in their time by killing sea-elephants and birds, making boots out of penguin skins to replace those that had been worn to pieces on the rocks, and visiting the wreck to salve whatever they could that might prove useful. Among the treasures they thus recovered were a few odd articles of clothing, some pieces of tobacco and bits of wood.

During January three huge icebergs sailed slowly by on successive days, heading northward. The largest passed a few miles away and seemed to be about 12 to 15 miles long and to tower about 1,000 feet out of the water.

Late in February a Swede named Tohure Lundstedt took ill. Nobody knew what the disease was. He grew steadily worse, but there was nothing that could be done for him. On March 1 he died. He was buried alongside Andersen, and wooden crosses made out of wreckage from the Seabird with their names crudely carved on them were placed upon the graves.

At intervals, when the food supply was approaching exhaustion, Hystad repeated the dangerous boat journey to Marion to fetch more. During one trip he was again marooned there for three weeks. He transferred six of his men at their request to Marion where they hoped living conditions would be better than on Prince Edward.

By the end of March life on Prince Edward had become intolerable. Gales were almost continuous, snow fell frequently and ice had begun to form in the pools. The tent had long since been torn to shreds by the wind, and the cave was the only protection from the elements that was left. Hystad therefore decided to evacuate to Marion and at the first favourable opportunity, on April 2, with his three boats and 13 companions he made his eleventh and last crossing of the channel. They reached Ship Cove safely and installed themselves in the huts.

Though conditions were better here, the cache of provisions was showing signs of giving out. With winter coming on the chances of rescue in the immediate future were growing smaller. But on the beach Hystad had found a 25-foot boat, possibly the one that Ree of the Solglimt had been fitting out for his proposed voyage of succour more than four years previously. He set to work to make it seaworthy, planning a desperate voyage to Cape Town to try to bring help to his men. He made primitive tools out of pieces of metal from the sealer's wreck, and for his timber requirements he broke down portions of the huts.

The Seabird's crew were so busy on this work that they failed to notice the approach of a ship. It was only when they heard the wailing of a steam siren that they looked up to see a whale-catcher approaching the cove. She was the T. W.l, another unit of Irvin and Johnson's fleet, specially sent from Cape Town in charge of Captain Carl Olsen (who had brought the Victoria down to Marion four years earlier) to look for them. The date was April 14, 1913, and the castaways had been marooned for just under six months. Their rescue had very nearly been postponed through the bunkers of the T. W. 1 catching fire only two or three days after she had left Cape Town. Her crew could not subdue it, and, stormy weather coming on, Olsen would have put back to safety had he not been able to picture well the need of the Seabird's survivors, if there were any, down on those islands. He forced his ship on while the crew played water on the heated coal, and on the sixth day out was within a mile of Prince Edward when a thick fog came down and forced him to pull away again until it cleared the next day. He interrupted the rejoicings of the rescued men by enlisting their help in moving the coal in order to get at the seat of the fire. By midnight it was under control. On April 24 the whaler brought the survivors safely back to Table Bay.

For a long spell after that the islands were left alone in their solitude. They did not come into the news again until 1929, when the British steamer Deucalion passed round them, intermittently sounding her siren and firing detonators, while her officers and crew searched the shores through glasses for signs of survivors of the Kobenhavn, the world's biggest windjammer, which had vanished on passage from the River Plate to Australia with nearly ninety Danes on board. The Deucalion, taking heed of the Admiralty Hydrographer's warning not to rely too much upon the chart, did not approach nearer the shore than two-and-a-half miles. She saw no signs of life.

The last record of men landing on either island was in November, 1930, when Irvin and Johnson sent their sealer Kildalkey to investigate the possibilities of resuming operations on them. She spent a month working off the east coast of Marion, but throughout that time was harried so much by gales that she had to shift position every few hours. In the end she gave up, her tanks unfilled, and set off homeward. The sea-elephants have since been left in peace.

Only two ships subsequently reported visiting the islands. The British Antarctic research ship Discovery II carried out some oceanographical investigations in the neighbourhood in 1935, and in October, 1940, the British cruiser Neptune, using the code-name Sule Skaer, made a secret passage from Simon's Town to look for Allied prisoners who, it was thought, had been put ashore there by German raiders. As conditions were unfavourable she made no attempt to effect a landing but steamed round both islands, sounding her siren and firing signal guns without bringing any response from the shore.

Copyright Mike Marsh (2025)