NO PATHWAY HERE

by John H Marsh

CHAPTER VI

COMMERCE AND METEOROLOGY

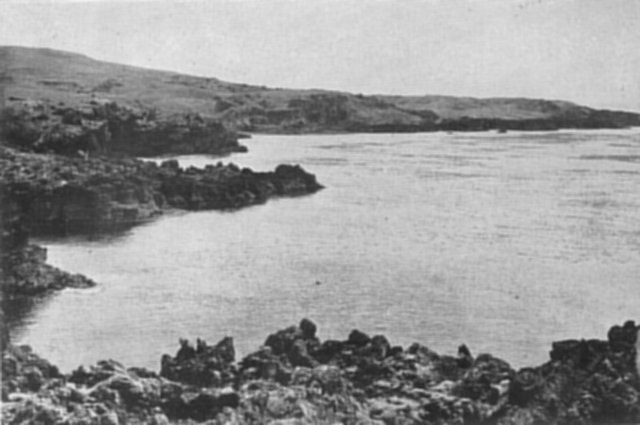

Fringing each island are high cliffs of jagged black lava rock,

with few breaks where landing can be made.

For all that, however, there were still some who believed that the Prince Edwards and other islands in the South African sector of the Southern Ocean had sufficient commercial value to be an asset to their nearest inhabited neighbour. This belief led Mr. H. Luhis, writing in "The South African Nation" in March, 1925, to urge that the Union should endeavour to acquire Tristan, Gough, the Prince Edwards and the Crozets. All these were British with the exception of the Crozets, which were French.

The Southern Ocean islands began about this time to arouse interest from an entirely different direction.

The development of wireless had given a spur to the science of weather-forecasting, since it was now possible to obtain up-to-the-minute reports of weather conditions at Sea and at remote points on the land surface of the globe. Many nations were now setting up weather-reporting stations on their territory. Those in the Southern Hemisphere had their eyes on the Southern Ocean and beyond, for there, all knew, their weather was born.

Efforts were soon being made to persuade the Union Government to establish a meteorological station on Tristan or Gough, as it was from their side that the westerly winds brought South Africa its weather. Negotiations with this aim in view were actually conducted with Britain in 1925, but were not carried to finality. It was only during World War II that a meteorological station was established there, mainly for war purposes.

The meteorological and its necessary adjunct, a radio station, were erected by the British Government, the Union Government giving all the assistance it could. A secret expedition to erect and staff them was fitted out at the Cape, and thereafter the Cape was the base from which supplies and reliefs were dispatched. Every possible precaution was taken to ensure that the enemy should not know the part that Tristan was playing in the war, partly because it would then lose much of its observation value, and partly because it might then draw upon itself vicious attack. At the request of British Naval Intelligence, South African newspapers until the end of hostilities avoided any reference whatever to the island.

Since South Africa was the chief and, really, the only country directly benefiting from Tristan's weather reports, her Government eventually agreed to provide the staff for the island's meteorological station. When the war ended and the British naval staff withdrew, she came to an arrangement with Britain whereby she took over the station, and she has been solely responsible for its maintenance since.

It was found that the weather conditions prevailing at Tristan were usually reflected in the conditions which obtained over the Western Cape three to four days later, and which subsequently moved eastwards right across Southern Africa.

The meteorologist's dream and the farmer's prayer have always been to have reliable weather forecasts not only three or four days, a week or even a month ahead, but a whole season and even more in advance. When adequate warning can be given of forthcoming droughts and floods, adequate preparations can be made to cope with them. An official of South Africa's Meteorological Department has stated that reliable long-range forecasts would save the Union's farmers an average of UK PNDS10,000,000 a year.

But the day of reliable long-range forecasting cannot come until there are sufficient recording stations, and they have been able to observe local weather conditions long enough to learn their effect upon other areas.

One of the Union's meteorologists on Tristan, Allan B. Crawford, was working for that day. He knew that if South Africa was to play her part in bringing it nearer, she must establish an adequate number of recording stations, widely scattered, in her own zone of influence. There were no other suitable land sites available to her to the west or south, other than Gough, but to the south-east there were the uninhabited Prince Edward Islands, over which Britain held sovereignty. They might be termed Tristan's opposite number, though they were nearer to the Union and further south than Tristan. Because they lay in the belt of the Westerlies the weather conditions ruling there must have considerably less direct effect upon subsequent conditions over South Africa than those at Tristan or Gough, though their influence might be quite strongly reflected during the rare and brief periods when gales blew up from the south-east. They would indirectly assist in forecasting the Union's weather by enabling an assessment to be made of the subsequent behaviour and movement of atmospheric disturbances observed at Tristan. Tristan's forecasts should thus in time become more rehable. Their real value, however, would be as necessary links in the chain of recording stations that must girdle the Southern Hemisphere in those high latitudes before medium- and long-range forecasting could become a practical possibility. All the countries in the Southern Hemisphere would benefit from it.

Crawford came back from Tristan and began to try to interest first his fellow meteorologists and then others of influence in the proposal that South Africa establish meteorological stations on Gough (which, though comparatively close to Tristan, was more suitable as an observation post) and the Prince Edwards. His efforts met with some success, and the proposal was eventually approved in principle. Early in 1945 he was instructed to assist Major Beadle of the same Department to collate all the information that could be obtained about the islands. With the aid of the public libraries they obtained access to all the books bearing reference to the islands that could be found. Although Gough was considered to be virtually unknown territory, only a handful of men having ever landed on it, they collected a fair amount of information. They had greater difficulty in digging out facts about the Prince Edwards.

Staffing and shipping shortages ruled out any possibility of the Union establishing more than one new ocean meteorological station at that time, and it was decided that Gough would be the better acquisition. Consequently the proposal to establish a station on the Prince Edwards was dropped, at least for the present. Plans for one on Gough were proceeded with, but finally they too were shelved at the Prime Minister's direction on the grounds of the expense involved.

Copyright Mike Marsh (2025)