NO PATHWAY HERE

by John H Marsh

THE VOYAGE

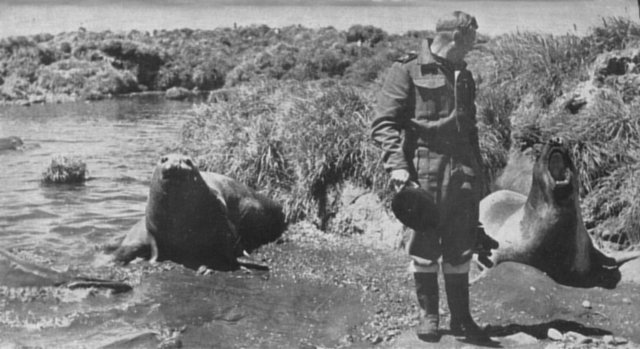

These females did not welcome the intrusion of Lieut. Bob Merry of the Natal.

ELECTRIFIED by the announcement that they were secretly to annex the Prince Edward Islands for their country, the men of the Transvaal animatedly discussed the prospect as their frigate breasted the Cape coast swells. This, then, was not just another harum-scarum exercise designed to test the efficiency of the ship and her complement. Here, instead, was the prospect of adventure unlooked-for even in these days of uncertain peace. They were quick to see a privilege in being chosen as pioneers helping to shape the history of their young nation.

To the four passengers who had come aboard before the departure from Cape Town, the Captain's announcement was also of considerable import. None of them were seafarers who might be expected to embark quite lightly upon an ocean voyage. Scarcely a day or two ago such a prospect was not even in their minds. Only 48 hours previously three of them had been occupying their desks in the normal course of their office routine in Pretoria, 1,000 miles inland from Cape Town.

One of these was Captain W. D. Anderson, S.A.E.C., Staff Officer (Engineers) to the Deputy Chief of the General Staff at General Headquarters. This one-time Rand gold-mining engineer with the walrus moustache was looking forward to leaving heat-baked Pretoria in a week's time to spend the New Year holiday with his family in Natal. This pleasant prospect was shattered when he was summoned by the D.C.G.S., Major-General Evered Poole, and told he was required to proceed to an undisclosed destination. There he was to investigate and report upon the possibility of establishing an aerodrome; obtaining a local water supply; using local vegetation for fuel; and using local materials for making concrete. He was also to report on the necessity for constructing bridges, roads and other means of communication. He was to co-operate with officers of the S.A.N.F. in reporting on the possibilities of using existing landing beaches and constructing a harbour; and with a representative of the South African Air Force in investigating the possibilities of building a seaplane base. All he could be told in advance was that he should take warm clothing with him, that he would probably be away for about a month and that he should be ready to leave immediately after lunch.

At 2.30 p.m. Anderson joined Commodore Dean at Waterkloof Air Station for the flight by special military plane to Cape Town. Commodore Dean had been called up from Cape Town by General Poole and was taking with him the orders for the Transvaal.

Also on the plane was Corporal R. J. Smith, of the South African Air Force (Cipher Branch). Like Anderson, he had received orders only a few hours previously to join the mysterious expedition. He had been told that his knowledge of ciphering would be of vital importance.

The third man to come down from Pretoria was Major J. A. King, a senior meteorologist attached to the Meteorological Office, which is administered by the Department of Transport. He flew down on the Saturday by mailplane. His instructions were to seek out a suitable site and report on the requirements for establishing a meteorological station.

A Cape Town doctor, Lieutenant Max Berelowitz, S.A.M.C., was seconded from Wynberg Military Hospital to act as Medical Officer of the Transvaal during her voyage. He had just returned from his honeymoon.

The last of the passengers to join the Transvaal was Captain D. A. Broadhurst, S.A.A.F. He had recently returned from navigating General Smuts to the United Kingdom. Now he was navigational instructor at Langebaan Airfield. He was to try to find a site for an aerodrome with a 2,000-yard runway at this place, the identity of which up to now had been unknown to him. He had tried to satisfy his curiosity after coming aboard by asking Fairbairn directly, "Where are we going?" The Captain, tapping the package of heavily sealed official envelopes under his arm, had replied: "You'll know in due course - it's all in here !"

Now that they had a definite aim for which to work, every man in the Transvaal's complement gave of his best. Large quantities of stores had come aboard shortly before sailing time and were stacked on deck. As they were heading for the open sea it was necessary to lash and stow these more securely. This work was put in hand at once.

The only guide to the Prince Edwards and information about them that Fairbairn had was a copy of the Admiralty chart drawn from the information supplied by the Challenger and heavily stamped with cautionary notices not to rely too much upon its accuracy; a copy of the "Antarctic Pilot"; and a single sheet of typescript containing a brief sketch of the islands' history.

At one time it had seemed that he would not even have a chart to help him. The Director had come from Pretoria with only a single copy, a photostatic enlargement of a tiny original. When he reached Cape Town and wanted to show it to Ryall and Fair. bairn, it could not be found anywhere. The Director worried not only as to how they were going to manage without it, but into what wrong hands it might have fallen. Only next day when he unpacked at home did he discover it tucked away among his clothes, where he had carefully hidden it!

The frigate followed the coast as far as Cape St. Blaize near Mossel Bay, where next day she took her departure from the African shore and headed south-east to make the crossing of the Agulhas Bank, notorious for its dangerous, confused sea, by the shortest route. In order to be ready for emergencies when they reached their destination, her crew spent the day renewing all the boats' falls, and overhauling their gear. The boats' anchors were replaced with larger ones and their anchor cables lengthened. Derricks were rigged ready for putting the dinghies and stores over the side.

On Tuesday, December 23, the Transvaal crossed into the "Roaring Forties". The weather now began to deteriorate, and the sea and air temperatures to drop sharply. For a time the ship ran through thick fog.

On this day Fairbairn and Grindley decided upon a plan of campaign which, they hoped, would find them prepared for every eventuality. They decided to carry out "Operation Snoektown" in four phases. Phase One was to be a reconnaissance to ascertain whether or not there were others already in occupation of the islands, and to find the most suitable place for landing. Phase Two was to be the actual landings and annexation ceremonies. For these the trawler boat was to be used. The crew picked to accompany Captain Fairbairn comprised Petty Officer Steward Henry Schott (whose choice of photography as a hobby was responsible for his being transferred from H.M.S.A.S. Natal at the last moment before the Transvaal's departure, supplied with extra movie and roll film, and ordered to make a photographic record of the annexation ceremonies); Petty Officer E. Sadler; Leading Seaman R. Terblanche; and Signaller D. I. Dally, who was to take with him the necessary equipment for maintaining visual communication between the landing party and the ship. Each of the boat's crew was to take with him three blankets, a ground-sheet, warm clothing, a torch and rations for 24 hours, in case they should be temporarily marooned ashore. First-aid equipment was also to be carried in the boat.

Phase Three was to comprise the landing of stores and equipment for the use of a small temporary occupation party, should it be decided later to put one ashore. It was necessary to prepare for such an eventuality well in advance, for they would require a tarpaulin; a wooden framework from which to make a tent; 14 boxes, each containing one day's rations for 12 men, and each carefully sewn up in waterproof canvas; three blankets for each of the men, also similarly protected; picks, shovels, hurricane lamps, heaters, stoves, paraffin, methylated spirits, matches, candles, ground-sheets, extra clothing and a medical kit. As there would be no facilities to help in landing all this, each package had to be small and light enough to be handled by one man.

The fourth and last phase would be the floating ashore of a flagstaff together with guys and gear for anchoring them, cement and paint. Eight men were selected for this job. The mast was to be made from some of the metal pipes that had been brought on board. The Engineer's Department undertook to fashion the metal anchor plates.

The plan of campaign, with detailed instructions, was notified to the ship's company without delay and preparations to put them into effect proceeded.

By noon on Christmas Eve the Transvaal had reached latitude 45 degrees South, and in his daily code message Fairbairn was able to radio that he expected to reach "William and Orange" at dawn the next day. "William" was the pseudonym that he had been ordered to use for Prince Edward Island and "Orange" that for Marion Island. He was not to mention their real names even in his code messages. It was hoped thus that even if by mischance the code were broken down, eavesdroppers would still remain in ignorance as to the exact locality of the operation.

The barometer was falling slightly, but as the weather was still reasonably good and there seemed a possibility of being able to effect a landing the next day, the cook was told that priority would have to be given to that operation, and he was accordingly to hold over his plans for serving a special Christmas dinner.

At the exact moment that Christmas Day was born, Marion Island was seen from the Transvaal for the first time. The radar operator picked up the faint blurr on his screen at a range of 46 miles. Ten minutes after midnight Prince Edward Island was contacted 22 miles off.

News of the landfalls spread quickly among those on watch. The South Africans considered the timing of the first sight of their future possessions to be a happy omen.

Dawn brought disappointment as many eyes scanned the sea for signs of the islands. It was raining, and visibility was low. There was no land in sight. The radar screen showed the islands still some miles off. The barometer had continued falling steadily through the night and had already dropped 17 millibars. With the dawn the wind began to rise. By breakfast-time it was blowing from the west at 35 to 40 miles an hour, and still freshening. On deck conditions were unpleasant.

At mid-morning those on deck caught a momentary glimpse, between the rain squalls, of the dark outline of land some miles away. It was blotted out again almost immediately. By midday the wind had reached gale force and visibility was reduced to between one and two miles. The Transvaal cruised round slowly, keeping constant radar contact with the land. At mid-afternoon Fairbairn decided that, as there was no sign of the gale moderating and because visibility was so poor and he had insufficient reliable data to guide him closer, it would be better to stand away and heave to in the open sea. Thus, cheerlessly, the South Africans spent their first Christmas in these waters. Their disappointment was only partly alleviated by the announcement that, as there seemed little likelihood of better weather on the morrow, they would partake of their postponed Christmas dinner on that day. During the night the wind eased slightly, but by dawn it was working up to a full gale again. The barometer was still falling. Throughout the day the ship remained hove to, rolling drunkenly over waves that were estimated to measure up to 30 feet from trough to crest. More than once she performed the rare feat of rolling her soundings boom under.

Despite the inconvenience and discomfort of eating on such a lively platform, the men did full justice to the excellent Christmas dinner turned out from the galley. All the messes were decorated with flags borrowed from the bridge, and the stokers' mess was the envy of all with its decoration of streamers produced from some secret cache.

So passed Boxing Day. With the coming of night the wind dropped considerably, but the barometer was still on the down-grade. At two o'clock the next morning it was down to 982 millibars - a drop of 39 millibars in 60 hours.

December 27 found the wind reduced to a light breeze, but the sea very confused and the swell heavy. Fairbairn decided to remain hove to. It was as well that he did, for there came rain, then sleet, then snow. The air temperature dropped to 39 degrees Fahrenheit - only seven degrees above freezing-point. A week previously they had been experiencing average temperatures of 70 to 80 degrees. The highest reading the thermometer gave on this day was 44 degrees. During the morning the wind started to blow and by noon was coming away from the west and the west-south-west at gale force. Now the barometer had begun to rise and early in the afternoon the wind dropped again to a fresh breeze. The Transvaal's men, however, got little comfort out of this, for it started to snow heavily. The sea remained confused.

On Sunday the elements relented, the wind dropping and the barometer appearing to steady. The frigate was able to approach the islands at last and give her men their first clear view of them.

Marion was a lovely picture. She rose, a jade jewel, out of the sea. Her lush green coat was fringed with the black lace of the cliffs and her heights draped in scintillating snow.

In comparison with the pyramidical appearance of Marion, with its cluster of nipples forming high peaks, Prince Edward was flat and unimpressive.

Fairbairn began his reconnaissance along the northern shore of Marion, carefully feeling with his Asdic for submerged dangers and searching the shore line for signs of possible inhabitants. He found a heavy swell running through the channel between the islands, and breaking in white-walled surges against the black cliffs near the Landing Place marked on the chart. With that surf it was obviously suicide to attempt to land there. Nor did he consider it safe to approach within a mile of the shore. He could find no good holding ground for his anchors. Had he got into difficulties he would have been in great danger of being blown by the north-westerly wind right into the trap formed by a submerged reef running out at right angles from the shore to the east of the Landing Place.

Continuing the reconnaissance along the north-eastern and eastern side of the island, the Transvaal soon had proof of the dangers confronting her because of the incompleteness of her chart. The Asdic gear installed to give warning of the presence of submarines now produced echoes which showed that the reef running northward from the vicinity of the Challenger's Landing Place actually extended at least a mile further out to sea than the chart indicated. Had she not been equipped with this tell-tale she might easily have been wrecked.

After reconnoitring right down the east coast as far as Cape Hooker, Fairbairn concluded that the north-east coast held the best possibilities for a landing under the existing conditions. He therefore turned about and radioed Waterkloof that as the weather was moderating he hoped to land in the afternoon on this section of the coast. He planned when he arrived off the area to send in the motor-boat for a closer reconnaissance.

Hardly, however, had the message gone forth for which the informed few in Pretoria had been waiting so long and anxiously, when the fickle weather changed. The wind veered to the north-north-west, ominous clouds banked up in the west, and heavy snow-clouds formed over the island peaks. The barometer began to fall rapidly. Soon violent wind-squalls were lashing the sea, and threatening to drive the frigate down upon a lee shore. Fairbairn had no alternative but to pull out again and seek what shelter was to be found about 20 miles away to the south-south-east of Marion. He spent the rest of that day and night hove to again, all hands by now being quite out of patience with the impossible weather conditions.

Copyright Mike Marsh (2025)