NO PATHWAY HERE

by John H Marsh

LANDING

MONDAY, December 29, brought an improvement in the weather. Aware by now that he must make the utmost of such an opportunity Fairbairn closed the land along the east coast of Marion and put out the motor-boat in charge of Grindley, for an inshore inspection. She reached the kelp line and had just begun to prospect for a possible landing place when there was a sudden violent shift of wind from the south-west. The recall signal was made at once. Within 20 minutes of being put into the water the boat was alongside again, but already there was such a seaway that great difficulty was experienced in hoisting her back on board. It was clear that, owing to the heavy swell and the absence of protection, landing on this part of the coast was impossible under those conditions. Fairbairn therefore headed north and approached the land again under the lee of the reef near the Landing Place, on the north-east coast. As ill-luck would have it his echo-sounder had temporarily gone out of commission, but he felt his way in with constant use of the deep-sea lead, until fairly good anchorage was found in 40 fathoms, on a bottom of fine sand and rock.

Through glasses a possible landing place was observed, sheltered on the north-west side by a high cliff. The motor-boat was smartly put over the side again, and Grindley made a close inspection from the kelp line. He returned shortly to report that the beach consisted of small round boulders, but he thought that the landing place was as good as any likely to be found.

At once Fairbairn ordered Phase Two of the plan of campaign to be put into operation. The "walkie-talkie" was installed in the motor-boat, which then towed the trawler-boat with Fairbairn and its picked crew as far as the kelp line. While the motor-boat waited in clear water, the trawler boat struggled to get through the weed.

None of the men had ever seen kelp like this before. It formed an almost solid barrier, stretched as far as the eye could see up and down the coast, and was about 50 yards wide. Later investigations showed that it extended right down to the sea floor, 15 fathoms below. From brown arm-thick stems, as stout as saplings, protruded stalks bearing large, spreading leaves each equipped with floats composed of a series of aircells within a thickened frond. When the oars caught under these stalks or stems, the only way to free them was to pull them out the way they went in. Progress therefore was slow and arduous. The men eventually gave up trying to row through the kelp, and resorted to digging the blades of their oars into the mass and levering the boat along in this way. So densely packed was the weed that a bottle thrown into the sea could not sink.

At last the little boat reached the shore, on which, despite the shelter provided by the promontory and the kelp breakwater, there was enough surf breaking to make it impossible to scramble on to the rocks without a wetting. One of the crew jumped over the prow to hold the boat off the rocks. His thrill at being the first to land was forgotten a moment later, however, when he heard a sharp bark and a loud hiss immediately behind him, and turned to look into the cavernous throat of a huge sea-elephant. The rock he thought he had jumped upon was the body of this brute, now rudely disturbed from his slumbers. The startled seaman was back in the boat again with more agility, if with less dignity, than ever he had embarked before! He could never thereafter be persuaded to land, and is said still to retain a peculiar prejudice agamst the island on which he helped to make history. While the others concentrated on keeping the boat off the rocks, Fairbairn and Schott scrambled out of reach of the surf and looked round for a suitable place for their two-man ceremony. The sloping beach, about 100 yards long and 30 yards deep, was composed entirely of lava boulders, worn round and smooth by the action of wind and sea, no doubt aided by the weight of sea-elephant that had wormed its way over them for centuries past.

Sixty or 70 of these huge mammals were occupying the beach at the moment. Some of the largest seemed to be nearly 20 feet long, and about ten feet in diameter, and they must have weighed well over five tons each. They lay slumped among the rocks just like great, overgrown slugs. The majority paid no attention to the intruders. Only those that were approached within ten or 15 feet troubled to raise their large, limpid eyes to stare curiously at the visitors. When approached more closely they made no attempt to move out of the way, but raised their bull-necked heads, opened their almost toothless jaws wide, and barked and hissed menacingly. Then, if given the opportunity to retreat, they would back away on their bellies by arching their torsos, slug-like.

In addition to the sea-elephants there were a few clusters of penguins on the beach.. These had even less fear of man than the mammals, and their curiosity so overcame some that the two men had difficulty in avoiding falling over them as they made their way over the rocks. On the shoulder of a cliff overlooking the landing place the men built a small cairn of stones. They planted in it the flag of the Union in metal and placed at its base, under heavy boulders, a brass plate bearing the inscription punched on it : "H.M.S.A.S. Transvaal, Date 29.12.1947." They had brought these ashore with them.

Fairbairn now read aloud the Deed of Sovereignty with which he had been supplied, as follows:

This flag has been raised on behalf of His Majesty's

Government in the Union of South Africa on this

fourth day of January, Nineteen Hundred and Forty

Eight, preparatory to the permanent occupation by the

Government of the Union of South Africa of this

territory known as Marion Island. This occupation

will take place within the course of the next few weeks.

(Sgd.) Lieutenant-Commander John Fairbairn,

S.A.N.F., Captain, H.M.S.A.S. Transvaal.

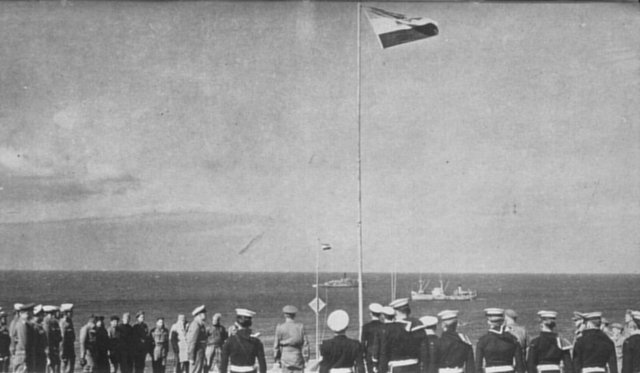

A stranger, looking down upon the beach and its neighbourhood while this ceremony was going on, must surely have sensed something incongruous about the whole scene. There was the naval officer, meticulously dressed, his uniform dripping sea-water and his limbs shaking in the bitter cold air, reading aloud a document with all the solemnity one might expect were his audience a society of philosophers rather than a crowd of slumbering sea-elephants, together with a few penguins and a non-commissioned officer, the latter carrying out the dual roles of witness and official photographic recorder. While his Captain read the Deed he was busy photographing him from all angles on stills and movies.

The document read, Lieutenant-Commander Fairbairn formally asked Petty Officer Steward Schott whether he had understood its import. Having received a reply in the affirmative, he signed the document with a shivering hand and inserted it into a brass cylinder that had been fashioned from a 4Omm. Bofors cartridge-case. Its brass plug was screwed into place and sealed with adhesive tape. Then the cylinder was buried in a disused penguin burrow, at the foot of the cairn, the entrance being sealed with heavy stones. Schott again recorded this operation on film. Thus, between landing at 11.32 a.m. and departing at 12.21 p.m. on Monday, December 29, 1947, Lieutenant-Commander John Fairbairn added to his country's possessions the sub-Antarctic island of Marion, and the first overseas possession of the Union of South Africa.

Solemnity and dignity were not in keeping with the character of Marion, and she soon diverted the attention of the annexation pair to the plight of their boat, which was in difficulties in the surf. Hurriedly they made for her, observing as they crossed the beach that it had obviously been used by others before, for there were large quantities of half-bricks and some steel plates lying among the rocks. They were quickly assisted into the boat, which by this time had taken some nasty knocks from the rocks, and had been holed. While some of her crew rowed, the others baled. Somehow they struggled across the kelp barrier, and the waiting motor-boat took them in tow. By the time they were brought alongside the Transvaal, however, all five men were standing up to their knees in icy water. All were wet through and suffering severely from the bitter cold. They had completed their task just in time, for now it began to rain, and then followed sleet and snow.

Fairbairn decided to suspend operations for the day. An hour after his return to the ship Waterkloof was receiving his long-awaited coded message announcing that Marion Island had been annexed, and that as the surf conditions were now unsatisfactory he proposed to postpone consolidating the annexation by erecting the main flagstaff until the following morning if weather conditions were then suitable.

Copyright Mike Marsh (2025)